Decoding the Renaissance: 500 Years of Codes and Ciphers

Why It Matters Who Wrote Shakespeare

Take a look at the photo above. It is ostensibly a graduation photo from 1918, but it actually is a secret message using a code Sir Francis Bacon created around 1575.

Now, you have a few choices here. You can stop reading and see if you can figure out the code and then read this article for the answer to the photo's riddle. You can cheat and browse the article looking for the answer (though I haven't yet decided if or how I'm going to reveal). Or, you can concentrate on the real message of this piece, which is an even bigger riddle: Why does it matter who really wrote the plays and poems attributed to William Shakespeare?

That riddle is the Holy Grail for so many so-called anti-Stratfordians who want to explain how a man of such obvious genius could be a glover's son from the middle-England burg of Stratford-upon-Avon with suspect educational credentials and who left behind little more in the way of manuscripts than sloppy signatures, as the so-called Stratfordians insist. The Stratfordians pooh-pooh all "authorship theories" by falling back on a well-established historical record that Shakespeare was a playwright as well as an actor, and a prosperous one at that, an argument (and a record) that the anti-Stratfordians say is part of a conspiracy shrouding the true identity of Hamlet's author.

And then a bunch of people out there—lovers of Shakespeare, included—ask, "why does it matter? Aren't the words more important than who wrote them?" The anti-Stratfordians tend to take greater umbrage at that question than the Stratfordians because by identifying their man or woman—whether it's Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, William de Vere (Earl of Oxford), Queen Elizabeth, or countless others—as the true author, we would glean truer meanings of those words.

I agree. Who wrote Shakespeare's works matters as much to me as what "Shakespeare" wrote.

All of this is a subtext in the Folger Shakespeare Library's current fascinating and fun exhibition, "Decoding the Renaissance: 500 Years of Codes and Ciphers," running to Feb. 26, 2015. If you are looking for the real Shakespeare, you'll find him here—but not, perhaps, where you might think you need to be looking. Like any good puzzle, right? Like any good poet, too.

A centerpiece of the exhibit is Bacon and his skills at creating ciphers, including a code much like the binary code computers use today. Bacon, because of his poetic talents and his ciphering skills, along with his alleged political views, was, other than Shakespeare himself, the first to be put forth as the actual author of Shakespeare's plays and sonnets. The case for him was first made in the early 19th century (more than 300 years after Shakespeare's death), but, though Marlowe and then Oxford overtook Bacon as favorites in the who-wrote-Shakespeare debate, the Baconians have recently gone the cryptographic route to remount their claim. This is not the first time Bacon's cyphering skills became the cornerstone in the authorship debate. In the early 20th century, an industrialist gathered a conclave of scientists at his Riverbank Laboratories near Chicago for various technological and literary studies, including a rigorous effort to decode Shakespeare's First Folio and find Bacon's secret cypher therein.

One of the men in that undertaking was William F. Friedman, who was trained in crop genetics but discovered he had a knack for cryptology—so much so that he went to work for the U.S. Army's Signals Intelligence Service when World War I broke out. He is one of the people sitting in the center of the photograph atop this article, and the Army officers are the graduates of his first course in military cryptanalysis. Friedman would go on to become the 20th century's foremost cryptographer, leading the team that broke the Japanese code at the start of World War II and creating a code for the U.S. military that neither the Japanese nor Germans broke. He also undertook a concerted effort to translate the Voynich Manuscript, a rare book carbon-dated to the early 1400s, written with characters so obtuse that it has baffled scholars and cryptographers since the book's discovery in 1912. Friedman and his wife, Elizabeth, also continued their studies of Shakespeare's First Folio, looking for Bacon's cyphers in the text.

The Folger exhibit, though, goes way beyond Shakespeare and Bacon. If you like puzzles, spies, the Renaissance, or World War II, "500 Years of Codes and Ciphers" is way cool. Curator Bill Sherman, head of research at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and professor of Renaissance studies at the University of York, has gathered for display all of the key Renaissance books on cryptography, most of them from the Folger Library and the U.S. Library of Congress next door. Among them are the oldest known text on cryptography and the first published text on the science as well as Bacon's 1605 Of the Advancement of Learning.

"The highest degree of cipher … is to signify anything by means of anything," Bacon wrote in 1623, and this exhibit shows Renaissance examples of such code-writing methods as nomenclator codes, alphanumeric tables, alphabet codes, stenography, steganography (codes in images), invisible ink, music, and flower arrangements (an interactive display lets kids "say it with flowers"). One 1542 document on complex cypher writing even comes from a resident of Stratford-upon-Avon, so ciphering was happening in Shakespeare's hometown before he was born. Sherman considers the exhibit's greatest treasure to be the Voynich Manscript itself, on loan from Yale University's Beinecke Library, the first time Yale has ever let the book out of its clutches.

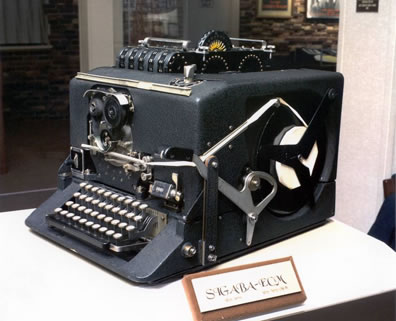

Above, the SIGABA cipher machine that William F. Friedman built for the U.S. military during World War II. The machine was not declassified until 2001. The SIGABA is on loan from the National Cryptologic Museum.

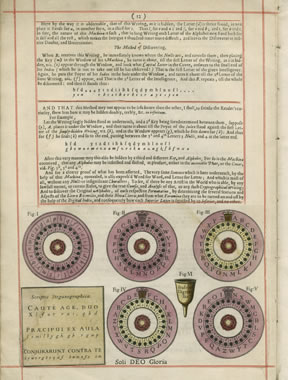

Right, a page from Samuel Morland's 1666 treatise A New Method of Cryptography with drawings of the cipherwheels he devised for his "Cyclologic Cryptographic Machine," a concept that Friedman used in his SIGABA. The Folger Library.

All of that alone could have created a worthwhile exhibit, but Sherman brilliantly goes beyond showcasing old tomes by paralleling the Renaissance riddlers with the 20th century work of Friedman, who drew on some of these same tomes for his own edification and inspiration. The exhibit includes graphs and cyphers Friedman created, from sheet music to dinner menus. His Christmas cards hid holiday greetings in word graphs, but he would send along a stencil card and instructions so the recipient could derive the right meaning.

Nothing illustrates the juxtaposition of 500 years of coding and decoding better than the SIGABA cipher machine in a display case next to Samuel Morland's A New Method of Cryptography, published in London in 1666. The latter is opened to a page with drawings of alphabet code discs, the same kind of device Friedman used when he built the SIGABA during World War II. Though SIGABA's patent is 2001, which is when it was finally declassified, Friedman used technology envisioned by a 17th century cryptographer.

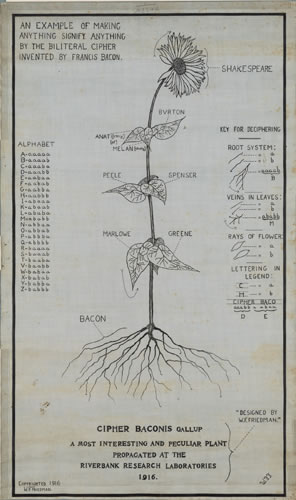

Similarly, this exhibit shows us how Bacon foreshadowed the invention of the computer. Bacon devised a biliteral cipher that used two letters, A and B, in five-character sets: the distribution of the two letters over the five characters determines its corresponding letter, from A (AAAAA) to Z (BABBB). For example, K is ABAAB, N is ABBAA, O is ABBAB, and W is BABAA. The order of the sequence is what matters, not their juxtaposition within a composition; in other words, the five-character construction could be scattered over a series of words or lines of poetry. It also doesn't have to be letters: it could be numbers, it could be words, it could be soldiers in a photograph facing toward the camera for A and looking to the side for B.

Friedman kept that photograph of the military cryptanalysts under a glass covering his desk. He saw its message, ascribed to Bacon, every working day (though he was five graduates—i.e., one letter—short, so the last word in the photograph is actually powe), and the full motto is inscribed on his tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery. Keying on that creed and dedicated to his hero, Friedman and his wife pursued the First Folio's secrets over the length of his career. They published their findings in a 1957 book titled The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined—to their chagrin, the publisher changed their preferred title, The Cryptologist Looks at Shakespeare, because while it might have been less enticing, the original title was more accurate. For, after a lifetime of examination, the Friedmans determined there were no "Shakespearean ciphers."

Still, you could say the ancient book with the greatest riddles on display in the Folger's exhibit hall is, in fact, Shakespeare's First Folio, ever present in its case in one corner of the room not far from where the Voynich Manuscript is currently borrowing space. And not only scholars but readers and audiences, too, have been decoding Shakespeare's ciphers for 400 years. But these aren't ciphers in the way scientists such as Bacon and Friedman see ciphers but in the way literary writers use them, as subtextual imagery.

The First Folio author went beyond using simple metaphors and similes in his works; he layered single metaphors in over-arching metaphors, nesting and stringing them together to create instant subconscious impressions while also planting memories that echo later in the play. In musical compositions this is called a leitmotif. In Bacon's words, this is a way to "signify many things by means of anything." It's how, for example, the rabble in Coriolanus becomes a pack of dogs and eyesight represents varying stages of wisdom in King Lear. However, more than just vocabulary factors into building these metaphorical arcs; because these works were written for the stage, the playwright used the sounds of words to build subtextual impressions—if not hidden meanings then contrasting or comparable meanings in the way we aurally process words in addition to how we intellectually process them. The Elizabethan theaters had no lighting effects and had limited sound and visual effects, so the very language of these plays became the green screen in the audience's minds: "Since a crooked figure may attest in little place a million, and let us, ciphers to this great accompt, on your imaginary forces work," says Henry V's Chorus.

And here's your modern parallel: I do the same thing. I recognized Shakespeare's use and distribution of imagery when I first started reading him in college, and from that time on I've used metaphors couched in allegorical sets strung on a leitmotif in almost all of my articles. I'm using metaphorical nesting in this article, probably less than I do in some of my writings, but more than in others (deadline pressure and mental acuity of the moment dictate the amount and effectiveness of their use). I also rely on the sounds that words make. I joke that I'm an alliteration addict—my son, Ian, will tell you I need an intervention session.

I am no genius; and I'm not humble, either. While I employ the same allegorical tricks Shakespeare used, however much I try I haven't yet reached the level of brilliance with which he employed them. On those occassions when I tap into a universal genius, it's as big a surprise to me as Christmas morning, a gift way beyond my mental grasp. As for my utilizing aural processing of words when I write, that comes from the fact that I am a slow, laboring reader; I hear the words I read more than I intellectualize their sentence's meanings. It's not so much a reading disability as how I learned to read, but the result is that I've had to put in twice the effort of my peers in school and work to achieve the same level of contextual understanding—that and, because I love music and play it as I work, I write with an auralscape and rhythm in my mind.

William F. Friedman worked up this "Cipher Baconis Gallup" diagram in 1916 when he began searchng for Bacon's ciphers in Shakespeare's works. With Bacon's binary code to the left, this diagram—representing Friedman's transition in scholarship from plant genetics to Renaissance cryptography—insinuates that Bacon was responsible for more than just Shakespeare's writing. Manuscript courtesy of the New York Public Library.

That's why it matters who wrote Shakespeare—it's not for the secret identity of the man behind the words but how and why a particular man wrote the specific words he wrote in the way in which he wrote them.

Even before computers came along, literature and linguistic scholars noted how Shakespeare's use of imagery patterns differed from those of his peers, including the works of Marlowe, Oxford, and Bacon; many computer studies using different algorithms have confirmed those conclusions. Furthermore, the imagery Shakespeare uses—in addition to the settings, characters, and dialogues—track singularly with the life of a glover's son from Warwickshire who worked in the theater, maintained both a business and a garden, lived in the London suburbs, and was familiar at court—all facts established in the historical record of the Stratford-upon-Avon native son named William Shakespeare (my imagery patterns track with being an Air Force chaplain's son who grew up in a transient household with lots of music, worked as a journalist associating with children with severe mental disabilities, rock stars, roller coaster designers, and U.S. senators, and has an incredibly hot wife). Shakespeare did not come of the noble class nor did he earn a university degree, and that's exactly why his characters speak the way they do; Shakespeare's works, including his poems, reveal that nature and human nature were his studies, lessons learned from everyday encounters. That is specifically what distinguishes his writing from that of Bacon, Oxford, and Marlowe (nobody in real life ever carried on conversations the way Marlowe's characters do), and it's one of the reasons Shakespeare's works remain so relevant and universal today. He was, and is, like so many of us.

The anti-Stratfordians disagree on who really wrote Shakespeare, but they all agree that Shakespeare couldn't have written Shakespeare based on three threads of evidence: that he had a lower middle-class, provincial upbringing; that he never went to university; and that he himself was not of noble peerage. To say these flimsy filaments are spun from pure snobbery is too pat; in fact, staking such a claim, burying Shakespeare in ultra-academic, über-romantic conspiracy theories, effectively denies the claimant his or her own human potential (unless the claimant is born into nobility, grew up in one of the world's leading cultural metroplexes, and excelled in college; then he or she is simply a snob).

In all the debate about who really wrote Shakespeare, there's one question I've never seen broached: Why pick on just Shakespeare? There is also question about the true authorship of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, but everybody else gets off unquestioned. There's no equivalent hand-wringing over who really wrote Chaucer; over Cervantes, Michelangelo, and da Vinci (all three with Renaissance upbringings and schooling that paralleled Shakespeare's); over Mozart, Beethoven, and Lennon; over Stephen King and J.K. Rowling; or over Orson Welles and Steven Spielberg. The historical record of William Shakespeare, playwright, is richer than all of his peers except self-promoter Ben Jonson, but nobody questions whether Marlowe wrote Marlowe or Oxford wrote Oxford or Bacon wrote Bacon (allegedly a master of ciphers; and Shakespeare had a cipher expert as a neighbor growing up—hmmm).

There's more historical evidence that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare than there is that Marlowe wrote Marlowe or Oxford wrote Oxford, let alone that either one wrote Shakespeare, yet the question still comes up, who wrote Shakespeare? It's like Lewis Carroll's Alice going down the rabbit hole—whoa, wait: did Carroll actually write Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, or was it Charles Dickens writing in code? Whoa, wait: did Dickens really write all those novels? After all, he had as little education as Mark Twain. Whoa, wait—no, stop! For if you deny the historical record for Shakespeare then you have to question the record of everybody else, from Chaucer to Spielberg to you; you'd have to question every piece of work by man.

If we can't look to the First Folio and see Shakespeare, we can't look at the Mona Lisa and see the peasant woman's bastard son who never went to university but mastered point-of-view perspective in his paintings and became the most amazing forward-thinking visionary of all time. We can't read Huckleberry Finn and see the Hannibal native who never made it out of grade school and cut his literary teeth as a territorial journalist before developing into America's greatest novelist. We can't listen to Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Opus 125, and see the deaf and depressed composer calling on every ounce of his musical and life experience to create the greatest score and most joyous piece of music known to man. We can't watch Saving Private Ryan and see the filmmaker who grew up as an Orthodox Jew in a broken family using his participation in the Boy Scouts to hone his skills at making movies. We can't take in Harry Potter and see the struggling single mother on the dole who, out of desperation and armed with a talent for turning phrases, created a stunning new world out of our world. If we can't look to the First Folio and see Shakespeare, we can't recognize the potential for true genius in our very selves.

That's why it matters that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare.

I likely will never reach Shakespeare's stature of genius, creation, or fame, but I at least know that I could do maybe more than he if I observe much, never let up trying, and keep pushing my internal envelope. That is mighty powerful knowledge to have, the kind that Bacon pursued and Friedman espoused and the son of a Stratford-upon-Avon glover achieved.

Eric Minton

December 3, 2014

.jpg)

*Photo from the William F. Friedman Papers, courtesy of the George C. Marshall Foundation, Lexington, Va.

Comment

Love your "Why It Matters." I'm always interested in the odd classism of denying someone as "lowly" as Shakespeare could write his plays, as it combines with a certainty that all those "hoity-toity academic experts" are trying to hide the truth of [insert alternative author of your choice here]'s authorship. It's truly a special place where American anti-intellectualism yet adoration of the aristocracy comes together.

Speaking of authors claiming Shakespeare's work as their own, I look forward to hearing what you think of Juliet's Nurse. The audiobook of the novel just won some award, which I find hilarious because it is read in a British accent, despite the fact that the narrator, and every other character, is Veronese. Sigh.

Lois Leveen

December 10, 2014

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances