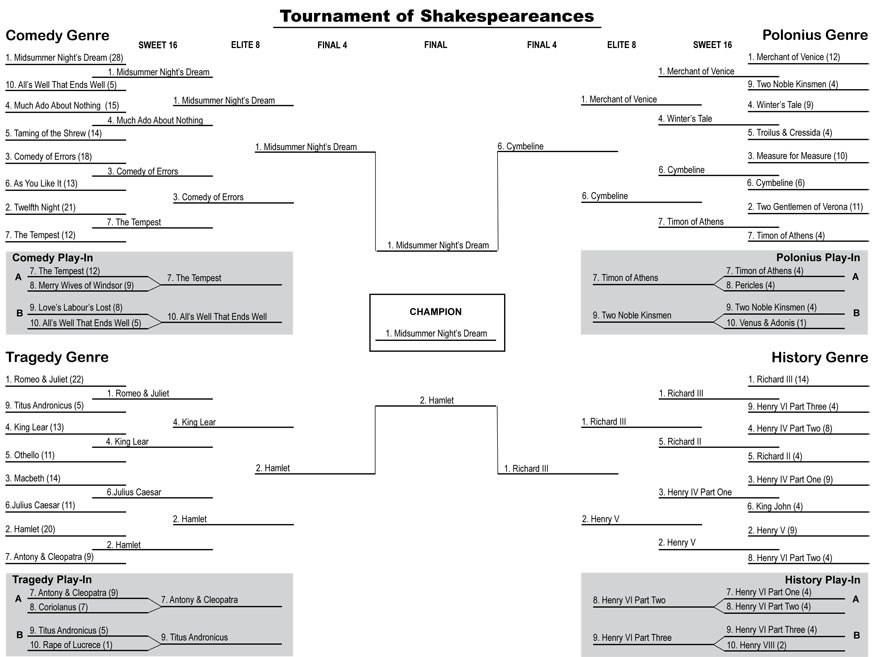

A Tournament of Shakespeareances

First Round: Upsets and Overtime

For a tournament overview, click here

For the tournament play-in matches, click here

Now that the Tournament of Shakespeareances is in full swing with the entire canon in play, we get a couple of evenly matched heavyweights going toe to toe and surprising upsets—surprising even me. Two number two seeds fall, and a number one needs overtime to advance to the Sweet 16.

Comedy Genre

The cast of A Midsummer Night's Dream at the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey. Photo by Brian B. Crowe, The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey.

1. A Midsummer Night's Dream (28) vs. 10. All's Well That Ends Well (5)—Don't think this lowest-versus-highest-seeds matchup is automatic. When I first read A Midsummer Night's Dream (sophomore year in college), I didn't think much of it. When I first read All's Well That Ends Well (senior year in college), I loved it. As this tournament is about the stage, not the page, the 2013 American Shakespeare Center (ASC) production of All's Well surpassed the long love I have for the play, which had been bolstered by the Shavian-style version the Shakespeare Theatre Company (STC) did in 2010. Still, there are just too many good Dreams. My collection of memories would allow you to pick actors in various productions to create a perfect ensemble, but three whole ensembles lead this play to an easy victory here: Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey's condensed traveling production in 2014 and Synetic's Silent Shakespeare version in 2013, and the production that topped my all-time Shakespeareances list for many years, the Atlanta Shakespeare Company's 1997 Shakespeare Tavern staging. When this play is firing on all cylinders, as that Tavern production did, it's hard to beat.

4. Much Ado About Nothing (15) vs. 5. The Taming of the Shrew (14)—Call this one the battle of the battle of the sexes, but other than that theme and the numbers of productions seen, this contest isn't close. From the 1987 Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) touring production with Nigel Terry and Fiona Shaw as Benedick and Beatrice to last month's Synetic Theater's Silent Shakespeare version set in 1950s Las Vegas, Much Ado has been much fun. Despite its archaic plot twists, it is Shakespeare's most consistent comedy, whether set in colonial Cuba, turn-of-the-century Italy, World War II England, a DC Caribbean community, a 1970s disco, a 1940s screwball film, or in modern L.A. The Taming of the Shrew is timeless fun, too (check out my commentary), as demonstrated by Synetic Theater's 2012 Silent Shakespeare staging and the ASC Actors' Renaissance Season troupe this year. However, most directors seem to keep it at arm's length, either in notably pre-feminist environments, such as the Old West (Theatre for a New Audience and Folger, both in 2012), or with feminist irony (RSC's 1978 Mafia Italy production with Jonathan Pryce as Petruchio). If more productions approached Shrew the way Chesapeake Shakespeare Company did last year, as an in-your-face romp, it would stand a chance. Instead, it is Much Ado that romps into the Sweet 16 to face A Midsummer Night's Dream.

3. The Comedy of Errors (18) vs. 6. As You Like It (13)—As You Like It brings an all-star lineup to this contest: Rosalind, Touchstone, Jacques, his “All the world's a stage speech,” and, I would argue, Celia. But except for the Shakespeare Theatre Company production last year and individual performances (such as Maria Gershuni's Rosalind at Brooklyn Technical High School in 2012, Lizzi Albert's Celia and Vince Eisenson's Orlando at Chesapeake Shakespeare Company in 2014, and Richard Katz's Touchstone with the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2011), this piece doesn't play as great as it reads. Comedy of Errors, on the other hand, plays far better than it reads, as Shakespeare scores a double-double doubled with his twin Antipholi and Dromios. From the 70-minute in-the-round production I saw back at the University of Missouri through the ASC's Looney Toons-like Actors' Renaissance Season production and Aaron Posner's Worcestershire Mask and Wig Society's version at the Folger, both in 2011, to Cincinnati Shakespeare Company's carnival-set production last year, Comedy of Errors is belly-laughing fun, easily beating As You Like It for a spot in the Sweet 16.

2. Twelfth Night (21) vs. 7. The Tempest (12)—It's the battle of the shipwrecks, Shakespeare at the height of his comedy writing powers versus his last solo composition. The Tempest on stage has much going for it: the actual shipwreck (ASC's 2011 production did it in the way Shakespeare's own company would have), a pageant of gods acted by spirits (STC's giant puppets were a highlight of 2014), and a collection of finely drawn characters of all ilk (Taffety Punk's production this year featured a strong ensemble revealing this play's rich treasure chest of characters). Twelfth Night needs to compete beyond its compositional brilliance, and it does when performed with the pureness of the Shakespeare Globe's production starring Mark Rylance as Olivia, earning him a Tony. It does when performed as landscape theater by New York Classical Theatre in 2012. It does when performed using Shakespeare's own production process by the ASC 2010 Actors' Renaissance Season troupe. It does when understudy Jeffrey Gruich and his dog kills as Aguecheek at Stratford Festival in 1994. It does when Herman Munster plays Toby Belch (Fred Gwynne) in the 1974 American Shakespeare Theatre production, my very first encounter with Shakespeare. Yet, too many directors seem unable to deploy Twelfth Night's attributes properly, over-emphasizing its darkness or adding extraneous stage business. Twelfth Night falls victim to bad coaching, and The Tempest pulls off the big upset, advancing to another battle of shipwrecks with Comedy of Errors.Tragedy

Faction of Fools' A Commedia Romeo and Juliet. Photo by Clinton Brandhagen, Faction of Fools Theatre Company.

1. Romeo and Juliet (22) vs. 9. Titus Andronicus (5)—It's not just that Titus Andronicus plays with such brute force but that Romeo and Juliet makes too many mistakes. Looking back at the R&Js I've seen, I wince more than I sigh. 2013 was a particularly bad period with the Carlo Carlei film and misfired stage productions on Broadway and at the Folger. Individual highlight reels notwithstanding—Jessica Aimone's nurse in the 2013 Brave Spirits production, Allison Glenzer's Friar at the ASC in 2013, Richard Katz's Capulet with the RSC in 2011, Nicole Lowrance's Juliet in PJ Paparelli's Columbine-inspired Folger production in 2005, Drew Reeves as Tybalt at the Atlanta Shakespeare Tavern in 2000, the swimming pool and red Ferrari in Michael Bogdanov's 1986 RSC production—most stagings of Romeo and Juliet are forgettable. Though seldom done, Titus is never forgettable, whether it's Brian Cox riding a ladder shackling the Goth prisoners in Deborah Warner's 1987 RSC production, Julie Taymor's 1999 film version, Victoria Reinsel's heartbreaking Lavinia at the ASC in 2009, or Douglas Overtoom's Titus serving the audience cookies representing human flesh in Dead Playwrights Repertory's 2013 version. Into overtime we go. Reading through my Productions Seen list, I notice how many adaptations of Romeo and Juliet are among my favorite representations of the play, from Rudolph Nuryev's ballet in the 1970s through Synetic Theater's Silent Shakespeare production in 2011 to Joe Calarco's Shakespeare's R&J at Signature Theatre in 2013. It is an adaptation that proves the difference here: Faction of Fool's A Commedia Romeo and Juliet in 2012 nailing the winning score over the swarming presence of that company's 2014 commedia dell'arte version of Titus Andronicus. The tragedy bracket's top seed survives to play another day, but Titus doesn't go down easily.

4. King Lear (13) vs. 5. Othello (11)—The first entry on my chronological list of King Lear productions is Trevor Nunn's 1977 RSC staging with Donald Sinden as Lear. It was the second Shakespeare play I'd ever seen but the one that turned me into a devoted fan of The Bard. In my early years, productions of Othello never resonated, but that tide turned with productions at ASC in 2010, the Folger in 2011, and Philadelphia Shakespeare Theatre and Brooklyn Technical High School in 2013. Meantime, Lear was floundering in overly conceptual productions (STC in 2009 with Stacy Keach, Theatre for a New Audience in 2014), or just bad performances. Only the Donmar Warehouse production we saw at BAM in 2011 came close to matching my love for the play, though Derek Jacobi whispered the heath scene. Othello zoomed to a seemingly insurmountable lead with the Q Brothers hip-hop version Othello: The Remix at Chicago Shakespeare Theater in 2013, a production I relive every time I play the original cast recording, and the Riverside Theatre in the Park production in Iowa City last summer confirmed Othello's stage greatness. But King Lear gets the ball for the last play, and what a play it is: Antoni Cimolino's Stratford Festival production last year with Colm Feore in the title role. Perhaps Othello simply ran short of opportunities, but King Lear moves on to face Romeo and Juliet in the Sweet 16.

3. Macbeth (14) vs. 6. Julius Caesar (11)—Julius Caesar was my first exposure to Shakespeare, in 10th grade. I hated it. Even as I later embraced Shakespeare, I never liked Caesar, and the RSC performance during the company's Park Avenue Armory residency was just the third time I'd seen the play. As for Macbeth, I loved it the first time I saw it on stage with the Oklahoma Shakespeare Festival in 1983, and the 2008 Idaho Shakespeare Festival production was the seventh confirmation. We even own the throne Patrick Page's Macbeth used in the 2004 STC production. The momentum shifted in 2012 when I reviewed the 1953 MGM film of Julius Caesar, with Marlon Brando as Antony, and saw for the first time the political machinations going on under the rhetoric. The next year came a string of stunning Caesar productions: ASC Actors' Renaissance Season, RSC's 2013 modern Africa-set staging at BAM, and the Donmar Warehouse women's prison production that we saw at St. Ann's Warehouse. Macbeth had suddenly fallen behind, though the Folger's 2008 production was, literally, magical, Alan Cumming's Macbeth in 2013 was a tour de force piece of acting, Kenneth Branagh's oversized production at Park Avenue Armory last year was impressive, and the ASC production last year had great Weird Sisters. Macbeth may be a timeless classic, but the second decade of the 21st century is Caesar's time, and thus does it pull off the upset and move to the next round.

2. Hamlet (20) vs. 7. Antony and Cleopatra (9)—The Cleopatra and Antony pairings I've seen include Glenda Jackson and Alan Howard (in a cast that included Patrick Stewart, Jonathan Pryce, Alan Rickman, and Richard Griffiths at the RSC in 1978); Vanessa Redgrave and Timothy Dalton (Theatre Royal Haymarket, 1986); and Judi Dench and Anthony Hopkins (National Theatre, 1987). Antony and Cleopatra has the twin power forwards or, at least, the towering Cleopatra at its center (Yanna McIntosh at Stratford Festival last year). Yet, even that all-star 1978 RSC production didn't fully gel. The Dench-Hopkins production is the only A&C that held my attention through the fifth act. Hamlet is philosophical and enigmatic, but it seldom fails to deliver excitement. I've seen three Hamlets at ASC (2009, 2011, 2014), all three directed by Jim Warren, all three different, all three great. I've seen a commedia dell'arte production by Faction of Fools in 2012 and a Silent Shakespeare production by Synetic in 2014: both great. I've seen a four-actor production by Bedlam, a one-man performance by Ted Van Griethuysen at STC, and a one-woman performance by Kate Eastwood Norris at the Folger: great, great, great. I've seen the Acting Company fuse Shakespeare's play with Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (Guthrie Theater, 2014) and a 30-minute student production at Brooklyn Technical High School in 2013; whatever, wherever, Hamlet proves to be a consistently great stage play. Caesar, beware the tides of March Madness!

History

1. Richard III (14) vs. 9. Henry VI, Part Three (4)—Here are some of the actors I've seen play Richard on stage: Antony Sher, Derek Jacobi, Ian McKellen, Tom McCamus, Kevin Spacey, and Mark Rylance—and, yet, none of these guys were the best Richard I've seen. For that, you have to start with Henry VI, Part Three (actually, Part Two, but it's competing elsewhere in this bracket). When the entire Henry VI trilogy is produced over the course of three successive ASC Actors' Renaissance Seasons by excellent actors with no director or design team and about a week's worth of rehearsal time for each play—the production process Shakespeare's own company used—all three plays turn out to be great fun, and the third installment in particular reveals itself to be a superb stage play. No wonder Shakespeare had to write a sequel to it, too. Match ASC's 2011 Renaissance Season production of Henry VI, Part Three, against any of those Richards I've listed above, and it wins. However, it can't beat it's own successor production the following year when many of its cast reprised their characters for Richard III with Benjamin Curns in the title role, who benefited from having played the character in the two prequels: that goes to the heart of why his Richard III tops all the rest and leads Richard III into the Sweet 16.

David Tennant playing Richard II at the Royal Shakespeare Company. Photo by Kwame Lestrade, Royal Shakespeare Company.

4. Henry IV, Part Two (8) vs. 5. Richard II (4)—I seldom do standing ovations, but I was on my feet at first clap when James Keegan finished his epilogue as Falstaff in the ASC 2010 production of Henry IV, Part Two. The first part of Henry IV is by far the better play, but Falstaff cements his status as the legendary comic character with Part Two. Thus I've seen sequels more satisfying than Part One at both the STC (Stacy Keach as Falstaff) and the RSC (Antony Sher as Falstaff), and Shakespeare's Globe (Roger Allam as Falstaff). I have never given Richard II a standing ovation, but Derek Jacobi's BBC version with John Gielgud as Gaunt certainly deserves one, as did RSC's recent production starring David Tennant, which we saw in a cinema broadcast. Those two productions, along with a 1987 RSC production with Jeremy Irons as Richard and a five-member-cast version at the Mary Baldwin College MFA Performance Festival last year, demonstrate how the all-verse Richard II, despite its formal pageantry and long speeches, translates into riveting theater. Despite Falstaff, Henry IV, Part Two, occasionally drags into tedium, and though it makes a late charge when Hal reconciles with the Lord Chief Justice (in the STC production) and rejects Falstaff (in the ASC production), it can't make up the difference. Thus does Richard II advance into the Sweet 16 to take on the other Richard.

3. Henry IV, Part One (9) vs. 6. King John (4)—Aside from King Lear, Henry IV, Part One is my favorite play. With Falstaff, Hal, the Hotspurs, Glendower, Henry IV, and, really, everybody else, it has Shakespeare's greatest collection of characters in an action-packed drama that also is the funniest comedy in the whole canon. Yet, when I conceived this tournament, I figured it would make a first-round exit. I've never seen any totally satisfying production; it's always played better in my head than anything I've seen. I've seen some fine Falstaffs, such as John Woodvine with the English Shakespeare Company (ESC) in 1986, Roger Allam at Shakespeare's Globe, and the ASC's James Keegan in 2009 and Rick Blunt in 2013. I've seen some interesting Hals (Michael Pennington with the ESC, Luke Eddy at ASC, Tom Hiddleston in the Hollow Crown series), good Hotspurs (Tim Piggott-Smith in the BBC version, Joe Armstrong with Michelle Dockery in the Hollow Crown), and a great Henry (Jeremy Irons in the Hollow Crown). But the whole never rose to the height of my expectations. However, Henry IV, Part One, drew the under-appreciated King John in the seedings. The ASC's 2012 production proves King John's worthiness, and Tom McCamus as John in the Stratford Festival's production last year scores lots of points, but though King John will exceed your expectations on stage, it still doesn't best a Henry IV, Part One, falling short of expectations.

2. Henry V (9) vs. 8. Henry VI, Part Two (4)—Henry V has common-class soldiers being pushed around by the nobles; Henry VI, Two, has a rebellion of tradesmen conquering London. HV has a king masquerading as a commoner; HVI-2 has lords insisting on their superiority before being killed for their arrogance. HV has two women telling dirty jokes in French; HVI-2 has a queen carrying and caressing the decapitated head of her lover in her husband's court. HV has Henry V; HVI-2 has Richard of Gloucester and Margaret, such great characters that Shakespeare would make them the focus of two subsequent plays. Henry VI, Part Two has its all-star production in ASC's 2010 Actors' Renaissance Season with an ensemble that had the audience enthralled, in stitches, and not wanting to wait another year for Part Three. Henry V has Kenneth Branagh. He scores a double-double, first starring in the RSC's 1985 stage production and then directing and starring in his 1989 film version. I've seen some other good Henry Vs, such as the ESC company's 1986 production with Pistol and his gang singing like English soccer hoodlums (“Thus come the English”), ASC in 2011, and Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF) in 2012. But Branagh is the difference maker in this contest, and Henry V moves on to the Sweet 16 to compete with his younger self.

Polonius

1. Merchant of Venice (12) vs. 9. The Two Noble Kinsmen (4)—After its blow-out victory in the play-in round, The Two Noble Kinsmen marches into this matchup against top-seed Merchant of Venice with deserved confidence. Led by the ascendant performance of Alison Glenzer as the Jailor's Daughter in the ASC 2013 Actors' Renaissance Season production (with Jenna Berk of the Brave Spirits 2014 production a strong force coming off the bench), Kinsmen also gets great play from David Mavricos and Willem Krumich as, respectively, Arcite and Palamon with Brave Spirits, and Eric Mills' Theseus and Nina Schrader Vitullo's Hippolyta in the Dead Playwrights Repertory 2013 staging. Noble efforts all, but they are up against such Shylocks as Al Pacino in the Public Theater production that moved to Broadway in 2011 (though he fouled out with the baptism scene inserted into the play), F. Murray Abraham in Theatre for a New Audience's revival of 2011, Antony Sher at the RSC in 1988, and Nigel Terry (with Fiona Shaw as Portia) at the RSC in 1987. Even the Jailor's Daughter can't supplant these Shylock scenes, and the Maryland Shakespeare Festival Bare Bard Repertory production's superlative fifth act in 2012 puts Noble Kinsmen away as Elizabeth Jernigan nails every shot Portia takes. Merchant wins its case and moves on.

Stephanie Holladay Earl as Hermione in The Winter's Tale at the Blackfriars Playhouse. Photos by Tommy Thompson, American Shakespeare Center.

4. The Winter's Tale (9) vs. 5. Troilus & Cressida (4)—The Winter's Tale dug itself a huge hole, first with the 1986 RSC production with Jeremy Irons as Leontes, Penny Downie as Hermione and Perdita, and Simon Russell Beale as the Clown: sounds impressive, but the only thing I remember of it is Downie's awkward doubling of Hermione and Perdita at the end (that's right: I don't remember Irons' performance). The National Theatre made some amends with its 1988 End Games Festival production, but next came an awful College of Charleston student production in 1993. Meanwhile, RSC's 1985 production of Troilus and Cressida with Alan Rickman as Achilles and gorgeous Lindsey Duncan as Helen is one of my faves, and the Shakespearean highlight of OSF's 2012 season was the Iraq War–set Troilus and Cressida. However, The Winter's Tale has made a late charge, with Greg Hicks' searing Leontes for the RSC in 2011, Jim Warren's sure-handed text-centric production for the ASC in 2012, and the Pearl Theatre Company's modern-dress, in-your-own-dining-room production this year. Winter's Tale squeaks by to take on The Merchant of Venice in the next round.

3. Measure for Measure (10) vs. 6. Cymbeline (6)—Measure for Measure is my third favorite play, and I have fond memories of so many productions: Michael Pennington as the Duke at RSC in 1978; a 1985 Young Vic production that reflected on the Margaret Thatcher government of hyper morality; puppets playing all the secondary roles in Aaron Posner's ingenious staging for the Folger in 2006; STC's intelligent 1920s Vienna cabaret-set production in 2013; and Fiasco Theater's six actors and six doors rendition at New Victory Theater last year. That's a formidable lineup. Cymbeline keeps it close, though, with the scrappy play of Judi Dench as Imogen at the RSC in 1979, ASC's 2012 romp, and Fiasco's landmark six-person staging that took New York by storm in 2012 (we saw it at the Folger last year). Measure for Measure is certainly the better play, but sometimes the underdog hits that miraculous winning shot, driving a stake through the better team's heart—or, in this case, an arrow through the magical trunk in Fiasco's production—and thus does Cymbeline advance to the Sweet 16.

2. Two Gentlemen of Verona (11) vs. 7. Timon of Athens (4)—That Two Gentlemen of Verona is a second seed astounds me. Why are so many theaters staging this flawed play? I admit that some have made it worthwhile watching, such as the RSC's modern Italy version last year, Fiasco's six-actors-on-a-bare-stage at the Folger, ASC's 2012 production with Glenzer's incredible Speed, Baltimore Shakespeare Factory's Ensemble Experiment presentation in 2012, and the poking-fun-at-itself musical, which I saw at the University of Missouri in 1979. Of course, if you want flawed, no play in the canon is more screwed up than Timon of Athens, which reads like a rough draft. At the least it needs a good editor, and in the ASC Actors' Renaissance Season last year, Benjamin Curns masterfully trimmed the play, and René Thornton Jr. led an all-in troupe of actors through what turned out to be a jaw-dropping character drama. The Public in 2011 with Richard Thomas in the title role also illustrates how much better Timon can be in the theater than in the library, but it was upon leaving the ASC production that I wrote, “I have just seen Shakespeare at his best, Hamlet and King Lear rolled into one with a bit of Much Ado About Nothing on the fringe.” That crushes any and all Two Gents I've seen, so Timon moves on for a showdown with another Cinderella, Cymbeline, in the Sweet 16.

Eric Minton

March 23, 2015

The Brackets

Click on the tournament brackets below to download a PDF version. The play titles on the PDF version are linked to their individual "Productions Seen" page on Shakespeareances.com.

For a tournament overview, click here

For the tournament play-in matches, click here

For results of the Sweet 16 matches, click here

For results of the Elite Eight matches, click here

For results of the Final Four matches, click here

For the result of the title match, click here

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances