West Side Story

Someday, Somewhere

Conceived by Jerome Robbins, Book by Arthur Laurents, Music by Leonard Bernstein, Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim

Signature Theatre, Arlington, Virginia

Tuesday, December 29, 2015, D–105 & 107 (left side of deep thrust theater)

Directed by Matthew Cardiner, Music Direction by Jon Kalbfleisch, Choreographed by Parker Esse based on the original choreography by Jerome Robbins

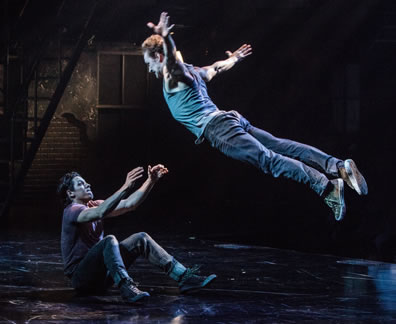

Maria (MaryJoanna Grisso) and Tony (Austin Colby) exchange vows with only mannequins as witnesses in Signature Theatre's production of West Side Story, the Jerome Robbins/Arthur Laurents/Leonard Bernstein/Stephen Sondheim adaptation of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Photo by Christopher Mueller, Signature Theatre.

Once you've attended performances of each play in William Shakespeare's canon, plus the narrative poems and the sonnets, and even works belonging to the Shakespeare apocrypha, what is left on the Shakespeare must-see list? One item would have to be the Broadway musical West Side Story, inspired by Romeo and Juliet and, to date, one of the best adaptations of a Shakespeare play.

It's taken me 58 years, but I finally saw the Jerome Robbins/Arthur Laurents/Leonard Bernstein/Stephen Sondheim masterpiece at Signature Theater last December. My review of that production got waylaid in the shuffle of this mortal coil, but now that I'm in the middle of a string of Romeo and Juliets (by the Chesapeake Shakespeare Company, the review of which I just posted, and upcoming productions at Kentucky Shakespeare Festival and by the American Ballet Theatre), I figured this would be a good opportunity to decipher my notes and let flow fond memories from that show six months ago, especially as its relevance is even more profound this week.

And, no, I've not seen the film version of West Side Story, either. I just never got around to it. We have the film soundtrack, which I listen to frequently, so I know and respect (for the most part) the music. Attending the Signature production was mostly fulfilling a checklist item, but as the production was advertised as "The Greatest Musical of All Time Like You've Never Seen It Before," I was curious as to how they would update a piece that, based solely on the film soundtrack, I considered stuck in its 1957 New York City setting (a bit of Wikipedia trivia: the musical's specific neighborhood setting was, even as the film was being made in 1961, being redeveloped as the Lincoln Center—how's that for dramatic irony?).

There's also irony in the theater's advertising pitch. "Like you've never seen it before?" Signature set out to stage West Side Story as close to the original production as possible, using the prescribed company of 30 actors and an orchestra of 17 musicians. Nor does this production change the original's time or place. The difference—and it's a big one (or, if you will, a significantly small one)—is that this version was presented on a deep-thrust stage in a 276-seat theater.

"Greatest musical?" That's like calling Hamlet Shakespeare's greatest play—there's plenty of viable reasons to call it so, but other works legitimately merit preference. Many landmark musicals have come before and since West Side Story rocked Broadway, London, and cinemas around the world. Still, there is no disputing this singular output from the collective genius of such theatrical and musical giants as Sondheim, Bernstein, Laurents, and Robbins—especially Robbins with his choreography combining jazz dance and ballet, creating some of the most resonating thematic ensemble numbers I've ever seen.

Add to this foursome the genius of the Signature production's choreographer, Parker Esse, who adapts Robbins' choreography to the small, deep thrust stage without sacrificing the awe. Director Matthew Gardiner also expertly works with the thrust stage so that no side of the audience is cheated out of seeing—and feeling—any of the action. I can't imagine "Somewhere" being more powerfully presented than with the company filling a rectangular stage and the audience in immediate proximity on three sides.

Ah, "Somewhere." "Somewhere, we'll find a new way of living. We'll find a way of forgiving, somewhere. There's a place for us; a time and place for us. Hold my hand and we're halfway there. Hold my hand and I'll take you there, somehow, someday, somewhere!" Did I mention how timeless is West Side Story? I came into this production thinking the opposite, but I was so wrong. Sondheim established his brilliance with his lyrics in this his Broadway debut. Meanwhile, Bernstein, the established maestro of the New York Philharmonic, concentrated all of his musical expertise—from Ludwig van Beethoven to George Gershwin to Charles Ives—on his most famous score, which flows arrestingly through symphonic melodies and discordant passages. Combine these two talents and you get the Jets being "Cool," but not so much, and you get "Maria" sounding like a soft prayer.

Of course, I wouldn't revel so much in the music, the lyrics, and the choreography if they weren't performed so well as this company does. It is Austin Colby as Tony who turns the name of Maria into a prayer, and MaryJoanna Grisso as Maria who sumptuously manages the vocal calisthenics of her role. Their voices blend beautifully; unfortunately, the chemistry isn't replicated in their acting. Stealing the show is Natascia Diaz as Anita, a role so rich it tends to win awards for anybody playing it, and Diaz infuses it with all the spunk and musicality the part requires (she was among the production's 10 Helen Hayes nominations, the Capitol Region's equivalent to the Tonys, but she lost out to the other-worldly performance of Kiss Me Kate's Robyn Hurder). Sean Ewing stands out as Bernardo, but the entire ensemble creates a solid corps in all facets: acting, singing, and dancing. Up in the loft above the stage, Jon Kalbfleisch conducts a tight orchestra creating a richer version of the score than what emerges on the soundtrack CD.

Splendid choreography by Jerome Robbins, adapted to Signature Theatre's thrust stage by Parker Esse. From top: the Jets, Kurt Boehm (Diesel), Colleen Hayes (Velma), J. Morgan White (Snowboy), Max Clayton (Riff), Ryan Fitzgerald (Action), Ryan Kanfer (A-Rab), Shawna Walker (Pauline), and Maria Rizzo (Anybodys); the Puerto Rican ladies, Jasmine Alexis (Teresita), Olivia Ashley Reed (Consuelo), Natascia Diaz (Anita), and Ilda Mason (Francisca); Ryan Sellers (Pepe) and Ryan Fitzgerald (Action). Photos by Christopher Mueller, Signature Theatre.

With costumes by Frank Labovitz and scenic design by Misha Kachman, this is the 1950s gangland of upper west side New York City where the Jets comprising Italian teens battle the Sharks, newly immigrated Puerto Rican teens, for turf and respect. Fiction derives from fact: The gang warfare was so prevalent at the time, it made headlines. Along with West Side Story, the situation prompted another American literary icon, David Wilkerson's The Cross and the Switchblade, published in 1962. It also prompted Bernstein's famous (and currently relevant) quote that the musical "will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before."

The gangs' "turf" battles actually were (and in the musical, are) outlets for the youth's feelings of social disenfranchisement, sense of dead-end economic prospects, and fear of lost cultural identity. Sounds familiar, doesn't it. The program notes for Signature's West Side Story contend that the musical mirrors current conditions. "A rapid rise in wealth inequality means more Americans increasingly find the American Dream out of reach. With their parents' inability to lift themselves out of poverty and provide for their children, today's disillusioned teenagers find solace in the gangs who provide them with a sense of family and security." It would be tempting, then, to actually update the musical in time and, perhaps, place; a bit of tweaking in the script and lyrics could alter the ethnic and racial compositions (and the names, too) of the Jets and Sharks.

However, part of what makes West Side Story so relevant, aside from its music, lyrics, and choreography, is its original time and place. History teaches us so much, especially when we see it repeating itself. Shakespeare never explains the origin of the discord among the Capulets and Montagues in Romeo and Juliet. "Two households, both alike in dignity," simply hate each other. Countless productions since Shakespeare's original have sought to find a basis for that hate, ranging from warring social statuses of old money versus new money to ethnic conflicts. All are apt specifically because Shakespeare didn't bother with the cause, only what results "Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean." He also focused his version of a well-established tale on how love can yet be forged in such discord. His play leads to tragedy for the lovers; it also leads to unification of the discordant houses because of the lovers.

That's the timeless lesson of Romeo and Juliet and West Side Story. In this day where black lives matter, blue lives matter, gay and transgender lives matter, all religious faiths matter, the "Western way of life" and Eastern cultures matter, and, particularly pertinent to West Side Story, immigrant lives matter, we need to find a new way of living, a way of forgiving, a time and place for all of us, somehow, someday, somewhere.

Eric Minton

July 11, 2016

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances