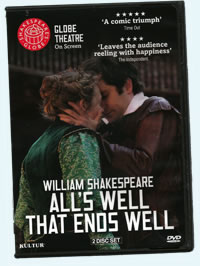

All's Well That Ends Well

Finding Feminism in a Slice of Elizabethan Life

Kultur/Shakespeare’s Globe (2013)

Directed by John Dove. With Ellie Piercy, Janie Dee, Sam Crane, James Garnon, Sam Cox, Michael Bertenshaw, Naomi Cranston, Peter Hamilton Dyer.

Like a good woman, All's Well That Ends Well is a beautiful thing, intelligent but with some baffling quirks, intriguing, fun to be with, and sexy. If that's sexist praise, blame William Shakespeare. He wrote a determinedly feminist play framed in a plot in which the women determinedly adhere to being the weaker sex and embrace a moral code enforced upon them by Elizabethan/Jacobean society in order to overcome the pandemic immorality of men. This feminist-in-misogyny reading surfaces thanks to the period costuming and textual purity of the 2011 production mounted by Shakespeare's Globe in London, the filming of which was released on DVD this year.

Like a good woman, All's Well That Ends Well is a beautiful thing, intelligent but with some baffling quirks, intriguing, fun to be with, and sexy. If that's sexist praise, blame William Shakespeare. He wrote a determinedly feminist play framed in a plot in which the women determinedly adhere to being the weaker sex and embrace a moral code enforced upon them by Elizabethan/Jacobean society in order to overcome the pandemic immorality of men. This feminist-in-misogyny reading surfaces thanks to the period costuming and textual purity of the 2011 production mounted by Shakespeare's Globe in London, the filming of which was released on DVD this year.

All's Well That Ends Well can be a difficult play to embrace. Evidence of that is the audience at this filming, sitting like toadstools with bored indifference. Meanwhile, I laughed my buttocks off watching the DVD, and for all the right reasons. This is a fine production with solid performances in almost every role, with stinging and poetic deliveries of the verse, and with direction by John Dove that allows the ridiculous main plot and hilarious subplot to unwind in sharp turns and surprising twists. A couple of choices don't quite work, but others that I was ready to write off as wrong boomeranged on me with point-scoring emotional punches.

Since the first time I read this play in my college days, it has been one of my favorites, though it has some flaws. Some of its poetry is among the best in the canon, and you could pull from this play a long list of beautifully phrased homilies to stick on your refrigerator. However, some passages read like they came from a hack writer, and the play's title is actually spoken twice, with a third verbal reference in the closing couplet. It's a good yarn, though the main plot is hardly timeless and requires much suspension of logic. Some of its characters are top-tier Shakespearean creations, such as the braggart-turned-penitent Parolles (played here by James Garnon), the exuberantly witty courtier Lafeu (Michael Bertenshaw), and the most singularly named of Shakespeare's richly detailed portraits, First Lord (Peter Hamilton Dyer). That he and the equally important Second Lord (Will Featherstone) maintain their generic speech headings, even after being identified as brothers by the name of Dumaine, is more indication of lazy writing, deadline-crunch composition, or a playwright struggling with disinterest in the play himself. This is the last of Shakespeare's romantic comedies, and most scholars put its composition in the period when he was delving into his great tragedies and character studies. All's Well That Ends Well seems to have been caught up in this creative transition.

That lapse in creative energy is nowhere more troubling than in the portrayal of the play's lead character, Helen. Schooled in medicine and stage-managing the play's plot with the felicity of a Prospero, she is arguably the most academically intelligent of Shakespeare's heroines. Her personality and skills earn her a mother's love from the Countess, the King's command, and the absolute fealty of strangers. And what does she spend it all on? Bertram, unarguably the biggest jerk to take the lead of a Shakespeare rom-com. Proteus is pretty dastardly in Two Gentlemen of Verona, but he at least has lust to blame for his actions; Bertram's motivations don't readily reveal themselves except that he's a jerk. Helen, however, not only dotes on him to distraction, she maneuvers to entrap him in a marriage he does not want and later gets pregnant as part of a ploy to keep him in the marriage.

These problematic lead characters create an almost insurmountable challenge for the actors playing them, and this production compounds the matter by mismatching the two performances beyond the gap of common sense and heart's nonsense with which Shakespeare saddles these characters. Ellie Piercy is certainly an intelligent Helen, full of charm and wit and adeptly balancing boldness with humility. In itself, hers is an entrancing performance, but she looks and plays as a woman nearing 30 while Sam Crane's Bertram looks and acts as if he's not quite 20.

I don't find fault in Crane's performance even if it is, for the most part, one-dimensional. Meanwhile, I endorse the choice to affix Bertram's overall behavior to being "an unseasoned courtier," as his mother calls him. This Bertram resembles the brash freshman at college or Bryce Harper making his Major League debut at 19. Crane gives a key reading to Bertram's interjection to the King of France after his royal highness has rambled on in high praise of Bertram's late father. "His good remembrance, sir, lies richer in your thoughts than on his tomb, so in approof lives not his epitaph as in your royal speech," Bertram says with forced patience as if he's heard enough of how great his old man was and wants to get out from under that shadow. His rush into manhood without the accompanying maturity is motivation enough for Bertram's subsequent actions, from refusing to marry Helen and running from her at the risk of being executed by the king to his so quickly giving Diana his heirloom ring just to get laid. Whether we accept this motivation as anything more than Bertram being a jerk is for us to judge, for Crane's one-note performance softens at the end into a moving portrayal of an honestly repentant young man. Notably, in the final scene when his marriage to Lafew's daughter is being discussed, Crane's Bertram is gazing dreamily at the ring on his finger, the token of his night with Diane (so he thought) but really the ring the King gave Helen who gave it Bertram in the bed trick.

The challenge for actresses playing the Countess of Roussillon is how monotonously dry the role can be. Aside from the scene in which she ferrets out Helen's love for Bertram, the Countess comes and goes in quick-spurt scenes offering lots of talk and little personality. That is, until the part is given to an actress with the skills of Janie Dee. The preshow establishes Dee's Countess as lonely, moving on with life while still grieving the loss of her husband and the pending departure of her son. About that son, she does not unduly dote on him (she is the polar opposite of Shakespeare's next great mother, Volumnia in Coriolanus). In the opening scene, she gives a gentle disciplinary slap to Helen (for seeming to grieve her father's death too much) and then another to Bertram on the line "Succeed thy father in manners [slap] as in shape." This slap is hard enough for Crane's Bertram to massage his jaw.

She finds new life in helping Helen pursue Bertram and is upset when Bertram flees the nuptial. Though Dee shows flashes of anger when discussing Bertram's behavior with the First and Second Lords, I initially thought she held too tight a lid on the Countess's perturbation over her "tainted fellow" of a son and his "wickedness … corrupt[ing] a well-derived nature." Dee, though, demonstrates that great acting is playing the character's whole arc, and when she comes on next with the news that now Helen has fled, this Countess comes close to a full-fledged meltdown. She clearly has come to regard Helen as her real daughter moreso than she regards her real son being Bertram. In the final scene, we see a weary, relenting Countess—until she discovers Bertram has Helen's ring from the King. At that point, Dee plays the Countess's lioness nature re-emerging. "Now, justice on the doers!" she says at the King's concern that Helen has been murdered, and Dee's accusatory glare at Bertram makes clear she'll testify for the death penalty in a heartbeat if he's "the doer." Keep an eye on the Countess even when she's silent: From the play's opening scene when she eyes Bertram with a hint of embarrassment to that suspicious glare in the final scene, Dee's expressions speak more meaningfully than the lines Shakespeare gives her.

This production's other great discovery is Sam Cox's King of France. Even on death's doorstep, this King's forceful personality keeps the courtiers in baffled abeyance. He wears his illness as a badge of honor, turning hospice care into a cavalryman's relentless charge into the inevitable end. As the lords take their leave, hoping "to return and find your grace in health," Cox shouts admonishingly, "No, no, it cannot be." Later in the scene when Lafew asks of the king, "Will you be cured of your infirmity?" Cox again roars a curt "No!" Stubbornness, not despair, is the attitude that greets Helen, and after her overly bashful entrance, Piercy's Helen suddenly takes the offensive in equal force to the King, accusing him of presumption and insinuating that his stubbornness is really fear of attempting her cure. As with the Countess, Cox's King begins to regard Helen as a daughter, and when cured, he not only now wears his health like a badge, he applies his fierce resolve to upholding her honor. In the last scene, while he offers words of reconciliation to Bertram, Cox delivers these lines tersely, highlighting his lingering disgust with the boy's behavior.

Dyer's and Featherstone's two Lords are disgusted with Bertram's behavior, too, but they noticeably hold back their condemnation publically when Bertram quickly becomes the Duke of Florence's favorite. They then turn the blame on Bertram's braggart companion, Parolles. The fake capture of Parolles, as he supposedly tries to rescue his unit's drum and the subsequent interrogation by the "foreign-speaking" lords, is a piece of stage business that can be as funny as Pyramus and Thisbe in Midsummer Night's Dream and the Cossack's visit in Love's Labour's Lost. It falls flat here, except in the performance of Garnon as the ever-flourishing Parolles with a noticeably thin veneer of bravery. Gardnon makes the veneer so translucent to everybody but Bertram, it's hard for us not to feel sympathy with this Parolles even before he is pranked into revealing his full duplicity. This not only allows us to believe his later repentance is honest, it puts us in his shoes. How many of us could be tripped up by our own bravado and lurking cowardice? How many of us live a lie that could at any time by any means—means beyond our imaginations—be exposed?

Helen (Ellie Piercy) promises that she can cure the King (Sam Cox) in the Shakespeare's Globe's production of All's Well That Ends Well. Below, Parolles (James Garnon) on his mission to recapture the drum as the other lords ready to "capture" him. Photos by Ellie Kurtz, Shakespeare's Globe.

Bertram is living in Parolles' shoes, but he doesn't know it. In that final scene, with us and him alone knowing the truth, our bile rises as we watch him layer lie upon lie, futilely fending off the accusations laid upon him. We therefore giggle at Diana's riddles (played by Naomi Cranston as a sexually eager girl resolved to do good), we smile at Helen's re-emergence, and we cry at Bertram's moment of real redemption. That we've arrived at this play's too-pat resolution in such a state is one of this production's crowning achievements.

All's Well That Ends Well wears its morality on its sleeve. It tackles disingenuousness, it smacks down social stratification ("Strange is it that our bloods, of color, weight and heat, poured all together, would quite confound distinction, yet stands off in differences so mighty," says the King when Bertram resists marrying "a poor physician's daughter"), and it bitchslaps presumption—literally in this production. Its centerpiece morality, though, is that of virgin's maidenhead. The women in the play hold it so dear that they go to great lengths to not only keep Diana's pure but also help Helen lose hers lawfully. Meanwhile, the play's two clowns, Parolles and the Countess's fool, Lavatch (here given an accessibly smart turn by Colin Hurley, who is helped by some judicious pruning of his part), persistently make fun of maidenhead's sacredness. Parolles even offers a sound logical argument against virginity. "Virginity by being once lost may be ten times found. By being ever kept, it is ever lost. 'Tis too cold a companion. Away with't!"

Amen to that! most of us 21st century viewers say (and Parolles' opinion was obviously shared by many an Elizabethan, including the supposedly upstanding Bertram). Helen's use of the bed trick to trap Bertram is therefore not something our mindset can easily embrace—nor, for that matter, is her dogged pursuit of Bertram and her entrapping him with marriage not once but twice. Her behavior we would regard as stalking today.

Amen to that! most of us 21st century viewers say (and Parolles' opinion was obviously shared by many an Elizabethan, including the supposedly upstanding Bertram). Helen's use of the bed trick to trap Bertram is therefore not something our mindset can easily embrace—nor, for that matter, is her dogged pursuit of Bertram and her entrapping him with marriage not once but twice. Her behavior we would regard as stalking today.

In the performance of Piercy as Helen in correlation with those of Dee's Countess and Cranston's Diana, we realize that virginity is the only currency these women have available to them, as it was with women in Shakespeare's Elizabethan-era society. Keeping it or losing it is their only track to power. Thus did Queen Elizabeth I choose virginity to secure England's throne at the cost of foregoing her own heir—given the timeframe of her rule (little more than half a century after the War of the Roses), that should give you an understanding of how dangerous Elizabeth's decision was and, consequently, virginity's ultimate value to her and her people. Otherwise, to us, it's hard to see how Shakespeare is using this social norm to empower the women in this play. But, in addition to presenting all the women as heroic protectors of their virtue, Shakespeare gives one woman (a commoner) the intelligence to cure a king; another woman (a commoner) the power to manipulate a titled soldier; and two mothers (the Countess and Diana's mother, given a comically stalwart portrayal by Sophie Duval)—both, notably, widows—the power to ensure that civilization passes to a capable next generation.

All's Well that Ends Well is, perhaps, an acquired taste. To borrow Hamlet's phrase, it is caviar for the masses, and maybe you have to be a Shakespeare connoisseur to get it. Well, if you are, get this one. The play is so rarely performed and has such scant screen presentations, and not only does this one requite Shakespeare's intentions well, it surfaces personalities and humor not so readily apparent on the page.

Eric Minton

May 24, 2013

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances